Introduction to Nidaros Cathedral, Trondheim and its relationship with St Magnus Cathedral, Orkney

Transcript of a public talk given to Orkney Archaeology Society, 27th November 2018.

By Dr Ragnhild Ljosland

Graffiti is so exciting because the walls talk to us, and by looking for and recording the graffiti, we are finally listening to them!

Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, Norway, is more or less contemporary with St Magnus Cathedral, and was its mother church in the sense that St Magnus Cathedral lay under the Archdiocese of Nidaros from its inception in 1153 until it was passed over to St Andrews in 1470 … although apparently the Vatican never took note of this, and has it under Nidaros right up until the Norwegian Reformation in 1530 (Charlotte Methuen). Nidaros Cathedral is the focal point of the St Olaf’s cult and we know that St Olaf was also worshipped in Orkney from the time of Earl Rognvald Brusason who had been fostered by Olaf from the age of ten and after Olaf’s death returned to Orkney to build the Olaf’s Kirk in Kirkwall in the 1040s. Orkney, and the St Magnus Cathedral in particular, therefore has very close ties with Nidaros Cathedral, so before embarking on the task of recording graffiti on the St Magnus Cathedral, we thought it would be useful to have a look at some of the marks on the Nidaros Cathedral.

Like the St Magnus Cathedral, the Nidaros Cathedral has a complex history of building, extension, decline and restauration. This is how it looked in 1762, before the great restauration works began. Therefore, some walls are much better than others for marks and graffiti.

Dedication inscription

The first inscription I would like to show you is not actually graffiti, but the cathedral’s dedication inscription. St Olaf died in the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030, and afterwards, according to legend, Torgils Halmason took his body to Nidaros, which is now the city of Trondheim, and hid the body in a shed before burying it in the sandbank by the river. There is holy spring with healing powers there, which is now built into a well in the choir of the cathedral.

Just like Thorfinn’s church in Birsay, the church in Nidaros was called Christchurch, and just like the Olaf’s church in Kirkwall, the church was probably initially built in wood, as was common in 11th Century Norway. However, in the 12th century it was replaced by a bigger and better stone minster. We remember from the Orkneyinga Saga Earl Rognvald Kali Kolsson promised the people of Orkney that he would build “a fine stone minster” to his holy uncle – There is a similar idea in Nidaros. Archbishop Eysteinn was the great church builder there. He was in office from 1157–88, so just after Rognvald’s time. In 1161, after a three-year journey to Rome to receive his office from the Pope, he was ready to consecrate the cathedral in Nidaros. This is the consecration inscription, in St John’s chapel in the south transcept. It reads, in Latin: “This altar was dedicated by archbishop Eysteinn in the first year of his episcopal office in praise of our Lord Jesus Christ, in honour of Saint John the Baptist and Saint Vincentius the Martyr and Saint Silvester, in the year of our Lord 1161 on the 26th November.”

The second inscription here is from a different church, Our Lady’s Church, another medieval church in Trondheim – I just thought I would include it for comparison. It is in Old Norse and on the outside East wall, and reads: “The holy Mary owns me, and Bjorn Signarsson made me.”

So unlike here on the Lady’s Church, Eysteinn’s inscription doesn’t say that the whole church is Olaf’s church – and indeed it’s really Christ’s church – but as with the Christchurch is Birsay it is now very closely associated with its local saint. We also see Olaf’s name in a piece of graffiti on the north wall of the chancel, near the octogon, where it says: “Olavus Halvardi”. This can be interpreted either as a name – of a pilgrim, perhaps – Olav Halvardsson; or we can note that the inscription contains the names of the two main Norwegian saints: St Olaf and St Halvard.

Mason's marks, hexafoils and crosses

Also belonging to the earliest history of the church are all these mason’s marks, left by the builders to show who had built what. We recognise shapes from the St Magnus Cathedral, such as the hourglass and the crow’s foot or m-rune.

The other day, during our Witch Trial Memorial creative day, with the Orkney Heritage Society, we had the pleasure of seeing this so-called “Witch’s Rose” next to the Paplay Tomb in the St Magnus Cathedral. It occurs, too, on the Nidaros Cathedral. It’s also called a daisy wheel or a hexafoil, and occurs in private homes as well as churches, as a mark of protection. The mark can act as a trap for demons by tricking the demon into following the lines, where it will walk in circles around the design forever more.

King Karl Knutsson Bonde's heraldic shield

This helmet and shield is perhaps the most exciting picture of all. It dates to around 1450, and the shield with the ship is the coat of arms of Karl Knutsson Bonde. He was a Swedish nobleman and one of the contenders for the crown during the union between Sweden, Denmark and Norway.

In 1448 he was recognised as King of Sweden, but he had a rival in Denmark: King Christian the 1st – the guy who pawned Orkney for his daughter’s wedding dowry! In Norway, Karl had the support of the Archbishop of Nidaros, Aslak Bolt, and Aslak crowned Karl as King of Norway in 1449. However, I didn’t manage to hold on to Norway, and was only king for a year. Christian then ruled in Norway, and seven years later Karl also had to give up Sweden to Christian. However, he got the Swedish throne back in 1467, three years before his death, while Christian of Denmark & Norway was busy trying to hold onto his dutchy of Schleswig-Holstein that eventually drained him of all his funds, so that he ended up pawning Orkney.

The two lutes

This is a section of the outside south wall of the nave, and if you look very closely, you will see two musical instruments. They are two depictions of the same instrument: A lute! Kate and Corwen and I were getting excited about this the other day, and they could tell me that the lute was originally an Arabic instrument called Al Ude, and it had come to Europe after the crusades. These pictures may date as far back as the 1300s. Look how detailed it is, with eight tuning pegs. The shape of the body is a bit unusual – They would normally not be as round, but more pear-shaped, so I don’t know how accurate a representation this is.

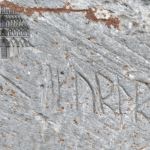

Runic medieval graffiti

Now, this is exciting for me. Runes! There are 38 runic inscriptions in total on the walls, plus one on a gravestone. I will not go through all of them, but just pick some favourites. Also, not all of them survive. There are some which were recorded in the past which are now lost, or they have been moved with their whole stone to the nearby museum.

This is the outside of the north wall of the nave. There has been some kind of altar here – You can just see the mark on the wall here. And around it, the wall is absolutely covered in graffiti. I like the many crosses: Greek cross in a diamond, roman cross with one leg, two legs, three legs. Another one of these swastika-like crosses. My favourite: Cross on a hill! Is it Golgata? But in amongst it all, a runic inscription is hiding. It’s really hard to spot, but Christopher of course spotted it with his magical eagle eyes. It says Lafrans – the name Lawrence.

And here, on the south wall, a Swede has written his name: Hávarð hǫgg – Håvard cut.

This one is near the main entrance, on the west wall below all the statues: Sigurd, followed by the letters ar.

I’m not sure of the entire text here, but I can see at least that this one starts with “pila” – which may be part of the word pilagrimr, pilgrim – Nidaros cathedral being the main destination for pilgrims in Norway.

Here’s one that captures a moment in time so beautifully. It was originally in a narrow corner between the octogon and the chapter-house. One summer’s night, on the saint’s day of St Olaf 29th July, two men were huddled into this corner, staying awake through the night – Trying to be as close to Olaf’s relics as they could without entering the church. “Jon and Ivarr held wake here on St Olaf’s night”. It has been taken out of its original position, and was damaged in the fire in the Archbishop’s palace in 1983, but luckily half of it was rediscovered in the excavations there in 1991, and is now on display in the museum that now occupies the new wing of the Archbishop’s Palace.

This one is also probably to a saint, rather than a personal name: Maria, St Mary, and a trefoil.

And here’s another moment in time: alabrum, early in spring! Or literally, early when the leaves are coming out.

This one has been moved to the Archbishop’s Palace museum, but was originally on the south face of the octogon, again as close as you can get to Olaf’s relics and his holy well without entering the church. It says: May God and the holy King Olaf help those men who carved these runes with their holy intercession.

These two are inside the Octogon, in the route that pilgrims would take around the shrine of Saint Olaf. “May God take Ketil’s soul” and “May God look after you, Erling Sigmundarson, now and forever.”

Finishing this tour of the runes with a dramatic story: These drowned in the fjord: John, Erik, Bishop Lodin, Chaplain …

Bishop Lodin was bishop of the Faeroe Islands from 1313-1316, until his dramatic shipwreck.

Medieval slander

Ok – Now over to some graffiti in the Roman alphabet. This one is the absolute highlight. It’s on that delightful outside south wall of the nave. Executed in beautiful letters and in Latin, someone has clearly had plenty time and taken great care to get this message across. However, now some of it is damaged. There has been a bit of discussion about this one, which Martin Syrett summarises nicely in his book The Roman-Alphabet Inscriptions of Medieval Trondheim.

The word that jumps out at you – at least at me, I may have a dirty mind – is ANUS.

What is going on here? Who are Laurentius and Petrus, or Lawrence and Peter, to use the English equivalents, and what are they doing??

Well – If we go with Macody Lund and read Laurentius Celvii, then Celvii may be an attempt to Latinise the patronymic Kalfsson. And Lawrence Kalfsson was a prominent Icelander who came to Trondheim in 1294. He had fallen out with the Icelandic bishop of Hólar, and fled to Norway with his close friend – guess who – Pétr Guðleiksson of Eiði, a Norwegian aristocrat. In Trondheim, Lawrence became a favourite of the Archbishop’s, but unfortunately got involved in further conflict, this time between the Archbishop and his canons. In the post of poenitentarius, which was more or less like a Depute Archbishop, Lawrence had to read out an interdict from the Archbishop, where he stripped the leading canons of their duties and incomes. You can imagine that this did not increase Lawrence’s popularity. After some turbulent years in Trondheim, Lawrence went home to Iceland and eventually became bishop of Hólar. (Martin Syrett, page 158-9).

The inscription, then, is what we call “nið”: A public slander, intended to destroy Lawrence’s reputation. “Lawrence Kalfsson is Peter’s arse” portraying him as being in a homosexual relationship with his close friend Peter Guðleiksson. This was NOT okay for a man of the church, or indeed for any man, in the 1290s, and a serious character assassination.

(If you want a thorough discussion of arguments for and against this interpretation, and alternative interpretations, see Martin Syrett’s book).

The people of Trondheim

There are lots of names, some of them with dates: Casparus, Andreas 1662, Johannes Winther 1729.

Here is someone called Erich, who has carved his name several times, alongside Peter. People liked to Latinise their names, so Peter here has chosen the Latin form Petrus, but on the right Peter. Erich has twice dated his inscription: 1730.

I like the beautiful handwriting in this one: F. Möller, 1846. Möller is the name of a prominent Trondheim family, who are best known as silversmiths. Established by Engelbreth Møller in 1770, their business is still trading today. In the Victorian period, they were busy getting rich and famous by riding the wave of National Romanticism, producing silver drinking horns and suchlike in the Viking dragon style for customers worldwide, including the Duke of Hamilton, the King of Siam and Andrew Carnegie.

The graffiti carries on into the modern day. Here is A.B.F. whoever that was, 1907.

And so the tradition continues today – I’ll finish off now with this very contemporary exclamation, which in a wonderfully ironic way contradicts itself: “Tagging er teit!” = Graffitiing is uncool! Which I hope to have disproven with my talk today: Graffiti can be very cool indeed.